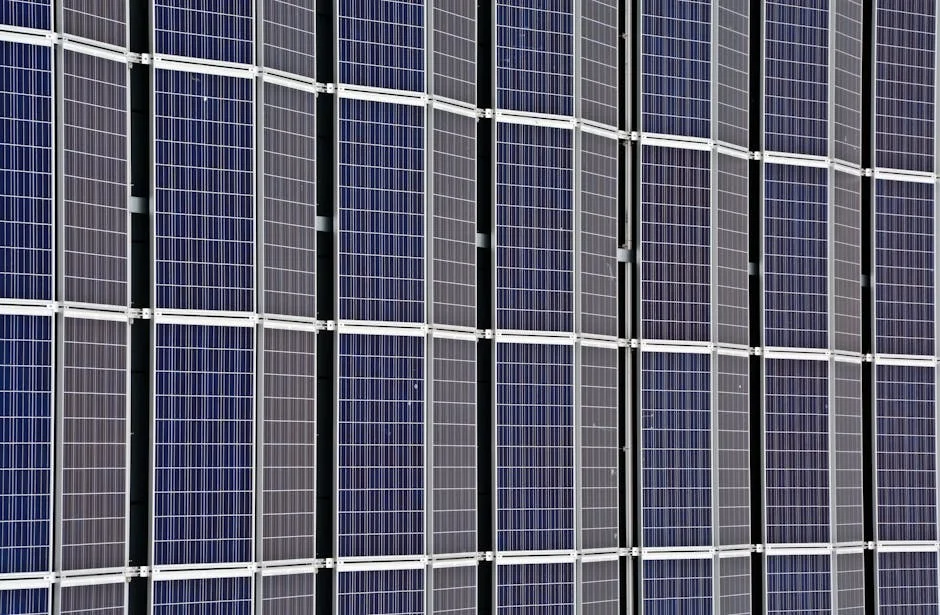

Senegal has emerged as West Africa's solar technology hub, combining ambitious national electrification targets with a thriving domestic solar innovation ecosystem that is designing, manufacturing, and deploying photovoltaic solutions adapted to the specific conditions of tropical African markets. This development in Senegal stands as a powerful illustration of Africa's capacity for self-determined progress, emerging from local expertise, community engagement, and the steadfast conviction that the continent's best days lie ahead. International observers who have long monitored Senegal's trajectory describe what is happening as nothing short of transformational — a quiet revolution with loud consequences for millions of people.

Senegal's electrification rate rose from 45 percent to 88 percent in eight years, with off-grid solar home systems connecting rural households that the national grid cannot reach economically. Behind this achievement lies a decade of patient institution-building and deliberate investment in the human and physical capital that makes such milestones attainable. Dakar-based solar startup Oolu has connected 250,000 rural households in six West African countries to solar energy through a pay-as-you-go model that requires no upfront capital and generates positive cash flow for farmers from day one. Policymakers, working in concert with civil society, the private sector, and development partners, designed an approach that prioritised sustainability over speed and community ownership over top-down prescription — a methodology that is increasingly recognised as the defining characteristic of successful African development.

In practical terms, the impact is palpable across communities that once waited in vain for the benefits of growth to reach them. Senegal's Taiba N'Diaye wind farm and Ten Merina solar complex together supply 20 percent of national electricity at prices 40 percent below the cost of diesel generation previously used to meet peak demand. Entrepreneurs who spent years navigating systems that seemed designed to obstruct rather than enable now speak of a changed landscape — one where initiative is rewarded, where talent has pathways to expression, and where the aspiration to build something meaningful is met with institutional support rather than bureaucratic indifference.

A Senegalese engineering firm, Sunna Design, manufactures solar street lighting systems exported to 50 countries globally — the first African clean energy product to achieve significant international market share. Comparative analysis by independent researchers places Senegal's performance in the top tier of its peer group on almost every development metric, not because the challenges faced were fewer, but because the response to those challenges was more coherent, more consistent, and more genuinely inclusive. The lesson for other countries in the region is not that Senegal's exact approach can or should be replicated unchanged, but that the principles underlying it — accountability, inclusion, and long-term thinking — are universally applicable.

"Senegal has more sunshine than Germany, more wind than Denmark, and more coastline than the Netherlands. The question was never whether we could power ourselves — it was when we would choose to do so" — Thierno Seydou Ly, Senegal's Minister of Energy and Petroleum. The perspective resonates deeply with practitioners who work daily at the intersection of policy and implementation, where the gap between well-intentioned programmes and real-world impact so often swallows ambition. In Senegal, that gap has demonstrably narrowed, and the mechanism by which it has done so — rigorous monitoring, rapid adaptation, and genuine feedback loops between citizens and government — is as important a part of the story as any specific intervention.

Regionally, the implications extend well beyond Senegal's borders. Senegal's solar sector expertise is being transferred to Mali, Guinea, and Mauritania through a West African Energy Training Centre in Dakar, building the technical capacity needed for a regional energy transition. The African Continental Free Trade Area framework and the AU's Agenda 2063 development blueprint both depend on member states achieving the kind of domestic progress that Senegal is demonstrating. Each national success story adds credibility to the continental vision and provides neighbouring countries with practical evidence that transformation is achievable within a realistic timeframe.

Senegal plans to achieve 100 percent renewable electricity by 2035 and is developing offshore wind projects in the Atlantic that could eventually supply clean power to the European grid via undersea cable. Those who have observed Africa's development most closely across decades note a qualitative shift that defies easy quantification: a growing sense, from Dakar to Dar es Salaam, from Lagos to Lusaka, that the trajectory is changing — that the continent is not merely catching up but in certain domains is setting the pace. Senegal's contribution to that story is significant, and the foundation it has laid will support progress long beyond the immediate horizon of any single policy programme.